|

Homeland Security

Securing Cyberspace Securing Cyberspace

President Bush appointed Richard Clarke to oversee the safety of the nation's computer networks. NPR's Larry Abramson reports for Morning Edition on the effort to secure cyberspace. Oct. 10, 2001.

The Politics of Security The Politics of Security

NPR's Don Gonyea reports for All Things Considered on the task facing the new director of homeland security, Tom Ridge, and the difficulty of coordinating some 40 agencies over which he has no statutory power or budget authority. Oct. 9, 2001.

More radio coverage on the U.S. politics surrounding America's response to and recovery from the Sept. 11 attacks. More radio coverage on the U.S. politics surrounding America's response to and recovery from the Sept. 11 attacks.

|

|

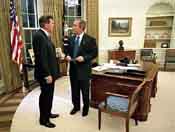

President Bush meets with Tom Ridge, the new director of homeland security, in the Oval Office.

Photo: Reuters © 2001

|

President Bush this week formally appointed former Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Ridge to run the newly created Office of the Director of Homeland Security, sending his close friend into the confusing and often rancorous turf battles of the federal bureaucracy, but without giving him much power to face the enormous challenges the job will present.

Bush also named two men to senior administration positions to help in the battle against terrorism. Retired four-star Army Gen. Wayne A. Downing is the new counterterrorism deputy at the National Security Council. Richard A. Clarke, who has worked for three presidents, was named special adviser to the president for cyberspace security.

The men will report directly to both Ridge and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice.

Downing spent 34 years in the Army, where he trained Army Rangers and eventually ran the Special Operations Command. Clarke, who worked in the State Department and the National Security Council for presidents Reagan, Bush and Clinton, was the national counterterrorism coordinator in Clinton's White House.

The men's duties are still not spelled out formally, and the lines of authority are less than clear. Each man faces immense challenges. Downing will help Ridge try to coordinate activities among several dozen federal agencies and departments involved in fighting terrorism. But with a small staff, no special powers, and an unknown budget, the office may have little clout among entrenched bureaucracies. In that way, it could become something like the office of the drug czar, which historically has been criticized as being a figurehead position. The Senate is considering whether to bestow more strength on Ridge's office, but in the meantime, it seems that the most powerful weapon in his arsenal is his friendship with the president.

Clarke's job is clearer -- but it will be no less challenging. He must work in the largely unregulated world of the Internet. Like Ridge and Downing, he'll have to employ his diplomatic skills to get cooperation from organizations with widely divergent interests -- in this case, private companies.

The biggest threat online comes from computer viruses, and Clarke will have to persuade software makers to change the way they create their products. Software is created for convenience and ease of use, not security. When security holes are found -- often by malicious people spreading viruses or cracking computer networks -- they are patched after the fact. Clarke will try to get software makers like Microsoft to start thinking more about security from the beginning, even if it comes at the cost of some convenience for users.

|